How Dual Coding With Teachers changed the way I present

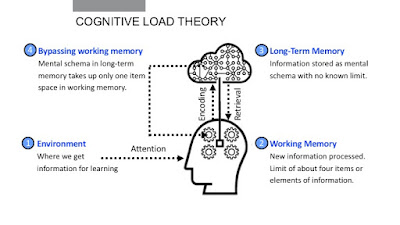

It was early 2019 that two things happened at about the same time. First, Edu-twitter was exploding with Oliver Caviglioli inspired graphics, and I was reading about Cognitive Load Theory, and planning to present on it at a conference. I ordered "the book" (Dual Coding With Teachers) but continued with my presentation after being inspired by the graphics I saw on twitter. My walls of text were transformed into the following slides.

After Dual Coding With Teachers arrived I analysed my slides agains the advice in the book, and saw the following problems with my slides:

- The fear of white space: Information was pushed right to the edges of the slides.

- The urge to cram lots of information in: There was too much information across the slides.

- The urge to be 'artistic': There was not a clear grid, and the slides were too random in the placement of information.

I already had my key content, but this needed to be rationalised, so I went about changing my slides in the following ways:

- Clarify purpose: Figure out exactly what it is that you want to communicate to the target audience.

- Organise sequence: Cull irrelevant and duplicated points, group ideas, and fit these ideas into a narrative.

- Align content: Fit the information into a grid

- Restrain design: Ensure that colours, images and text are consistent, and leave plenty of white space.

The result was that the original six slides were condensed into one slide shown below. When I presented on this slide I discussed most of the information on those original six slides, but in a more coherent way which didn't overwhelm the audience with slide fatigue.

I originally thought that Dual Coding with Teachers would help me to improve the design of my presentation slides, which it did, but it provided more than that. The process of organising information simply and visually helped me to clarify the information I wanted to share, in both my own thoughts, and within the presentation.

If you haven't purchased a copy of Dual Coding with Teachers yet, I can't recommend it highly enough. I think it has value for anyone who presents information in any profession.

Dan (@dan_braith)